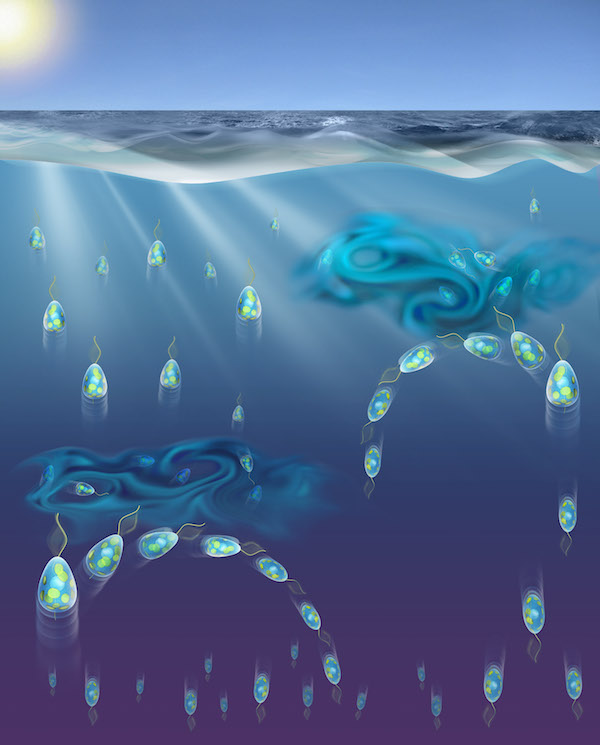

Unicellular photosynthetic microbes—phytoplankton—are responsible for virtually all oceanic primary production, which fuels marine food webs and plays a fundamental role in the global carbon cycle. Experiments to date have suggested that the growth of phytoplankton across much of the ocean is limited by either nitrogen or iron. But simultaneously low concentrations of these and other nutrients have been measured over large areas of the open ocean, raising the question: Are phytoplankton communities only limited by a single nutrient?

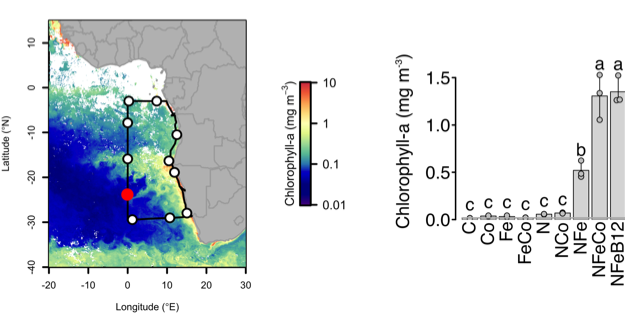

Authors of a study recently published in Nature tested this by conducting nutrient addition experiments on a GEOTRACES cruise in the nutrient-deficient South Atlantic gyre. Seawater samples were amended with nitrogen, iron, and cobalt both individually and in various combinations. Concurrent nitrogen and iron addition stimulated increased phytoplankton growth, yielding a ~40-fold increase in chlorophyll a. Supplementary addition of cobalt or cobalt-containing vitamin B12 further enhanced phytoplankton growth in several experiments.

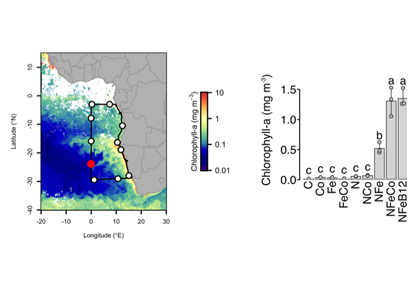

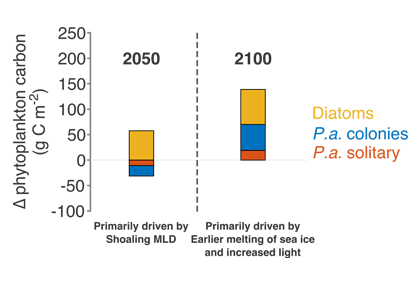

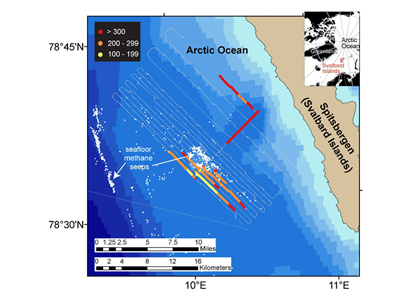

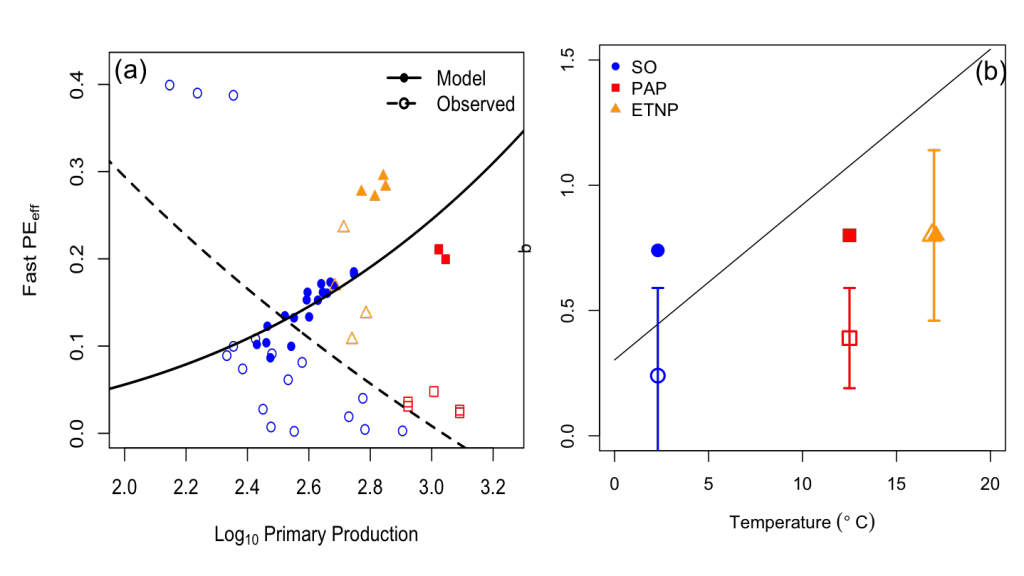

Experiments conducted throughout the southeast Atlantic GEOTRACES GA08 cruise transect (left panel) demonstrated that nitrogen and iron had to be added to significantly stimulate phytoplankton growth (right panel). Supplementary addition of cobalt (or cobalt-containing vitamin B12) stimulated significant additional growth.

In addition to co-limited sites, the study identified ‘singly’ and ‘serially’ limited sites. These limitation regimes could be predicted by the measured ambient seawater nutrient concentrations, demonstrating the potential for using nutrient datasets to make confident predictions about limitation at larger spatial scales, an approach that is being more widely used in programmes like GEOTRACES,.

Finally, a complex, state-of-the-art biogeochemical ocean model suggested a much smaller extent of nutrient co-limitation than the experiments indicated. Authors attributed this to relatively restricted microbial and nutrient diversity in the model. These findings have implications for how such models are constructed if they are to represent nutrient co-limitation in the ocean and accurately project changes in ocean productivity in the future.

Authors:

Thomas J. Browning (GEOMAR)

Eric P. Achterberg (GEOMAR)

Insa Rapp (GEOMAR)

Anja Engel (GEOMAR)

Erin M. Bertrand (Dalhousie University)

Alessandro Tagliabue (University of Liverpool)

Mark Moore (University of Southampton)