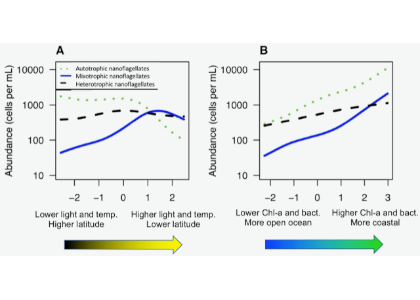

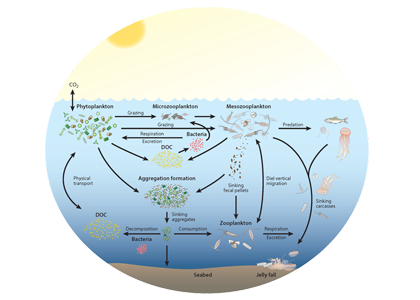

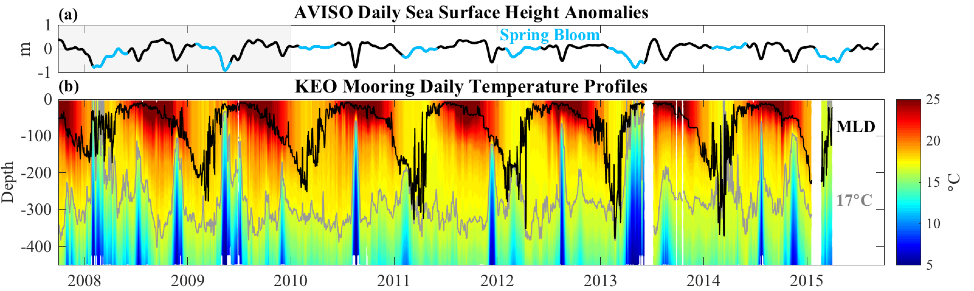

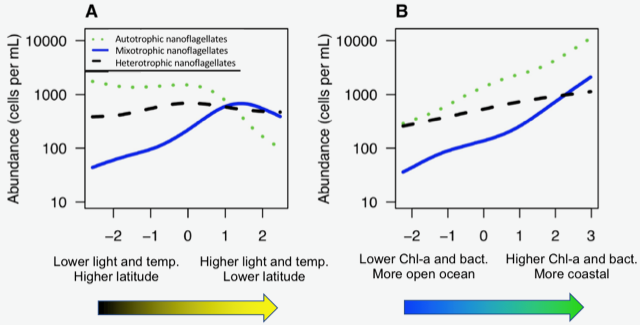

In the ocean, unicellular eukaryotes are often mixotrophic, which means they photosynthesize and also consume prey. In recent decades, it has become clear that mixotrophs are ubiquitous in sunlit ocean habitats. Additionally, models predict that mixotrophs have important impacts on productivity, nutrient cycling, carbon export, and food web structure. However, there is little understanding of the environmental conditions that select for a mixotrophic lifestyle, and it is unclear how mixotrophs succeed in competition with autotrophic and heterotrophic specialists. A recent study in PNAS that synthesized measurements of mixotrophic nanoflagellates showed that mixotrophs are more abundant in stratified, well-lit, low latitude environments (Figure 1A). They are also more abundant, relative to pure heterotrophs, in productive coastal environments (Figure 1B). A trait-based model analysis revealed that the success of mixotrophs depends on the fact that they are less nutrient-limited than autotrophs (due to prey-derived nutrients) and less carbon-limited than heterotrophs (due to photosynthesis). This synergy requires sufficient light, leading to success in low latitude environments. Similarly, a greater supply of dissolved nutrients relative to prey, as commonly observed in coastal environments, favors mixotrophs relative to heterotrophs. One implication of these results is that carbon fixation at lower latitudes may be enhanced by mixotrophy, while limiting nutrients may be more efficiently transferred to higher trophic levels.

Figure 1. Estimated abundance of autotrophic, mixotrophic, and heterotrophic nanoflagellates across environmental gradients in the ocean.

Author:

Kyle Edwards (Univ. Hawaii at Manoa)