One of the biggest unsolved mysteries in climate science concerns the dynamics and feedbacks of the ice age carbon dioxide (CO2) cycle.

At the height of the Pleistocene ice ages, the atmospheric CO2 concentration was about 1/3 lower than during the warm interglacial periods. Most scientists think that the CO2 that was missing from the atmosphere was in the deep ocean, but how and why remains unclear. In a study published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, we compared different computer simulations of the ice age ocean with δ13C, radiocarbon (14C), and δ15N data from sea floor sediments.

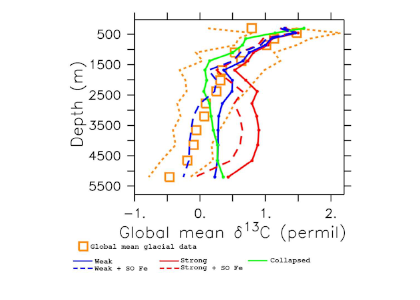

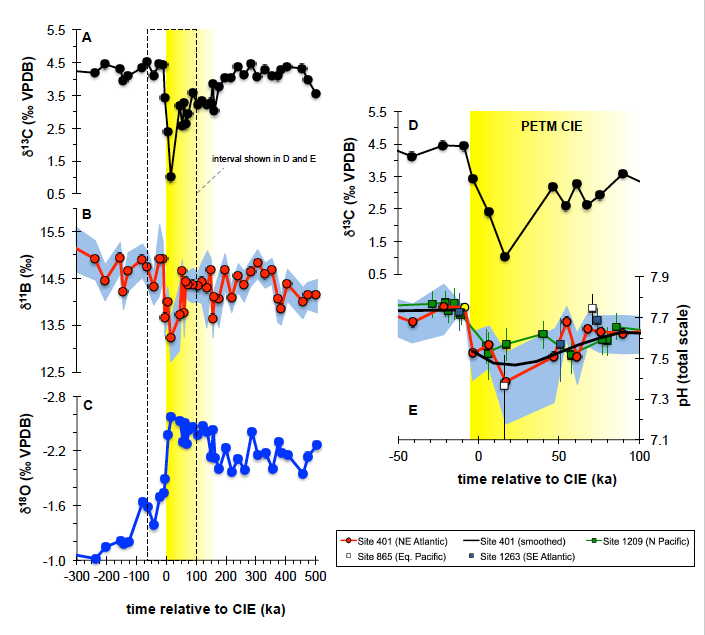

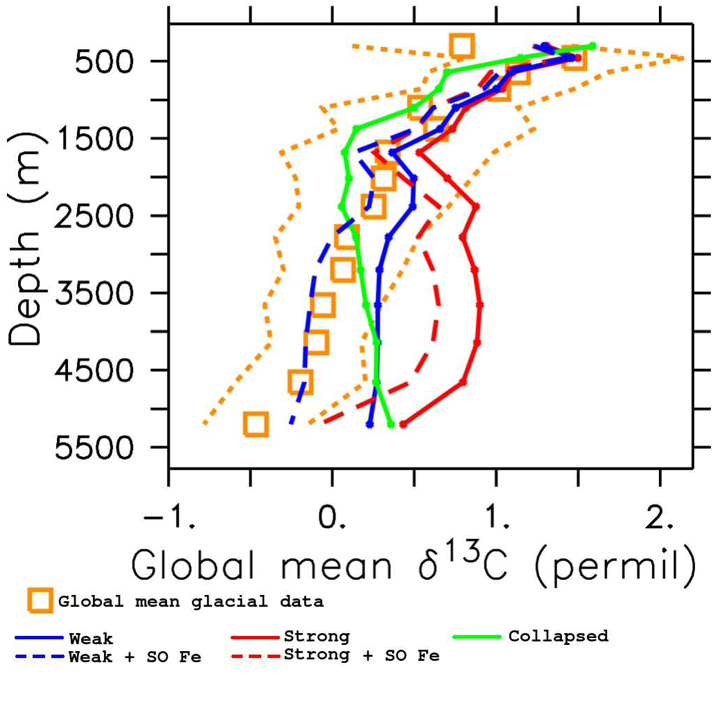

We find that a weak and shallow Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (6-9 Sv, or approximately half of today’s overturning rate) best reproduces the glacial sediment isotope data. Increasing the atmospheric soluble iron flux in the model’s Southern Ocean intensifies export production, carbon storage, and further improves agreement with glacial δ13C and δ15N reconstructions.

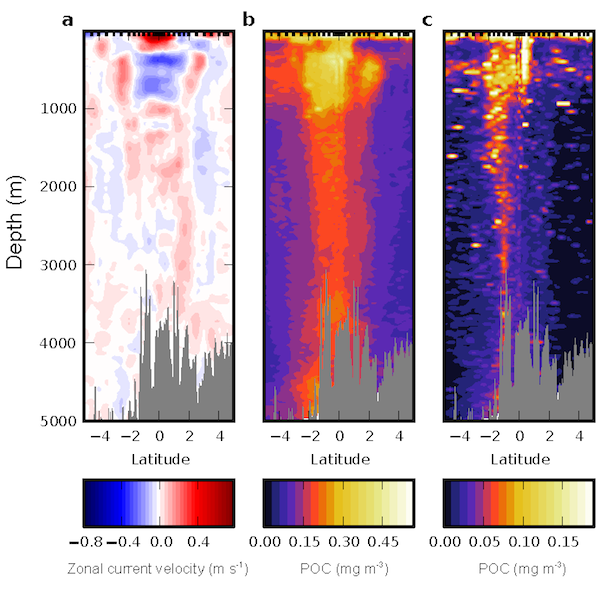

Figure Caption: Depth profiles of global mean δ13C, calculated using only grid boxes for which there exists Last Glacial Maximum data. Blue: Weak Atlantic circulation; Red: Strong Atlantic circulation; Green: Collapsed Atlantic circulation; Dashed: Extra iron in the Southern Ocean; Orange: Last Glacial Maximum Data.

Our best-fitting simulation (blue, dashed line in the figure) is a significant improvement over previous studies and suggests that both circulation and export production changes were necessary to maximize carbon storage in the glacial ocean. These findings provide an equilibrium glacial state, consistent with a combination of proxies, that can be used as a basis for simulations covering the last deglaciation time period. Understanding the different states that the global climate system can transit, and the characteristics of the transitions, is crucial to project possible outcomes of current climate change processes.

Authors:

Juan Muglia (Oregon State University)

Luke C. Skinner (Godwin Laboratory for Palaeoclimate Research, University of Cambridge)

Andreas Schmittner (Oregon State University)