Tropical cyclones (hurricanes and typhoons) are the most extreme episodic weather event affecting subtropical and temperate oceans. Hurricanes generate intense surface cooling and vertical mixing in the upper ocean, resulting in nutrient upwelling into the photic zone and episodic phytoplankton blooms. However, their influence on the deep ocean is unknown.

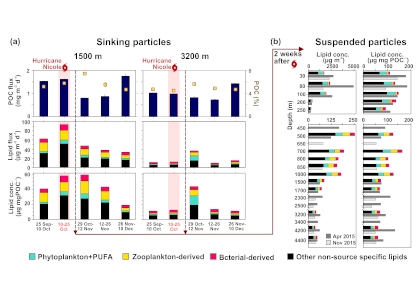

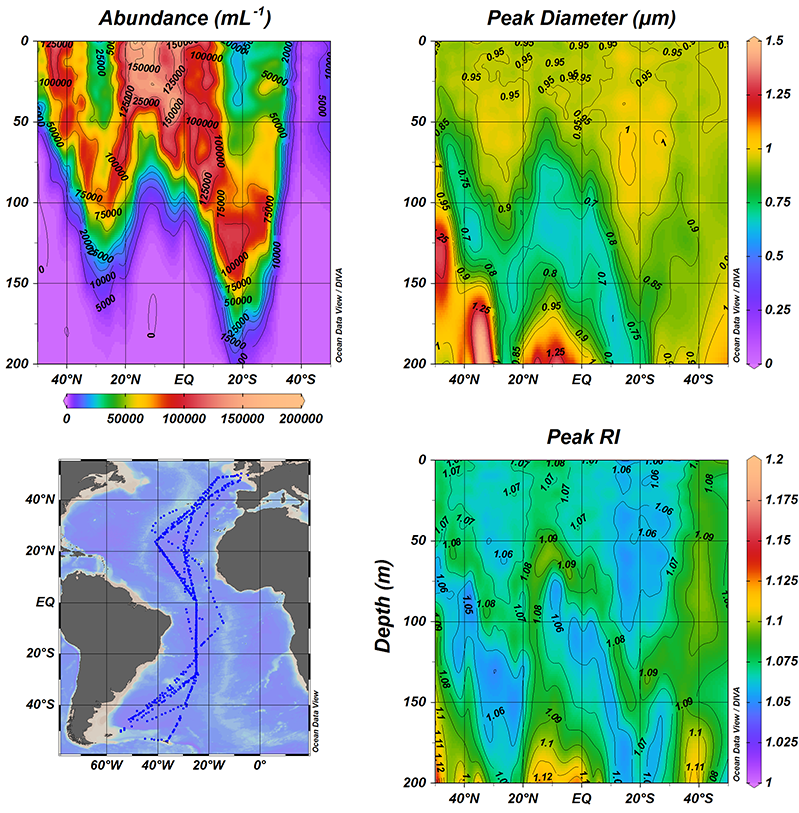

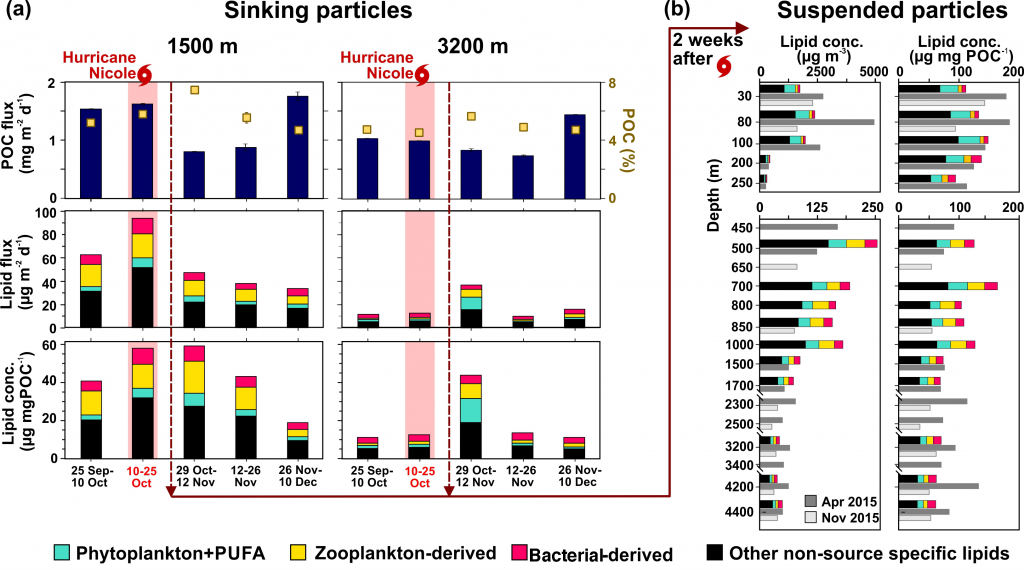

Figure 1. (a) Particulate organic carbon (POC) flux and percentage of the total mass flux (yellow) (top panel); fluxes (middle panel) and POC-normalized concentrations (bottom panel) of diagnostic lipid biomarkers for phytoplankton-derived and labile material, zooplankton, bacteria, and other (see legend); (b) Lipid concentrations (left panel) and POC-normalized concentrations (right panel) of diagnostic lipid biomarkers for the same sources as in (a) (see legend) measured two weeks after Nicole’s passage (25-29 Oct. 2016). Shown for reference are total lipid concentration profiles in April 2015 (dark gray, typical post spring bloom conditions) and Nov 2015 (light gray, typical minimum production period).

In October 2016, Category 3 Hurricane Nicole passed over the Bermuda time-series site (Oceanic Flux Program (OFP) and Bermuda Atlantic Time-Series site (BATS)) in the oligotrophic NW Atlantic Ocean. In a recent study published in Geophysical Research Letters, authors synthesized multidisciplinary data from hydrographic and phytoplankton measurements and lipid composition of sinking and suspended particles collected from OFP and BATS, respectively, after Hurricane Nicole in 2016. After the hurricane passed, particulate fluxes of lipids diagnostic of fresh phytodetritus, zooplankton, and microbial biomass increased by 30-300% at 1500 m depth and 30-800% at 3200 m depth (Figure 1a). In addition, mesopelagic suspended particles were enriched in phytodetrital material, as well as zooplankton- and bacteria-sourced lipids (Figure 1b), indicating particle disaggregation and a deep-water ecosystem response.

These results suggest that carbon export and biogeochemical cycles may be impacted by climate-induced changes in hurricane frequency, intensity, and tracks, and, underscore the sensitivity of deep ocean ecosystems to climate perturbations.

Authors:

Rut Pedrosa-Pamies (Marine Biological Laboratory)

Maureen H. Conte (Bermuda Institute of Ocean Science and Marine Biological Laboratory)

JC Weber (Marine Biological Laboratory)

Rodney Johnson (Bermuda Institute of Ocean Science)