Sinking particles are a critical conduit for the export of material from the surface to the deep ocean. Despite their importance in oceanic carbon cycling, little is known about the composition and seasonal variability of sinking particles which reach abyssal depths. Oligotrophic waters cover ~75% of the ocean surface and contribute over 30% of the global marine carbon fixation. Understanding the processes that control carbon export to the deep oligotrophic areas is crucial to better characterize the strength and efficiency of the biological pump as well as to project the response of these systems to climate fluctuations and anthropogenic perturbations.

In a recent study published in Frontiers in Earth Science, authors synthesized data from atmospheric and oceanographic parameters, together with main mass components, and stable isotope and source-specific lipid biomarker composition of sinking particles collected in the deep Eastern Mediterranean Sea (4285m, Ierapetra Basin) for a three-year period (June 2010-June 2013). In addition, this study compared the sinking particulate flux data with previously reported deep-sea surface sediments from the study area to shed light on the benthic–pelagic coupling.

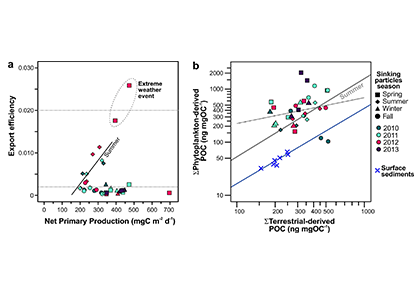

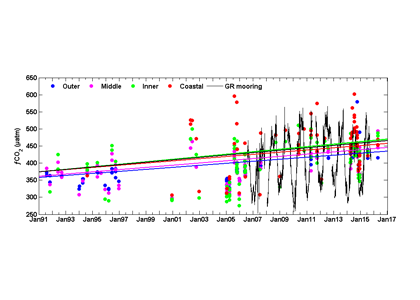

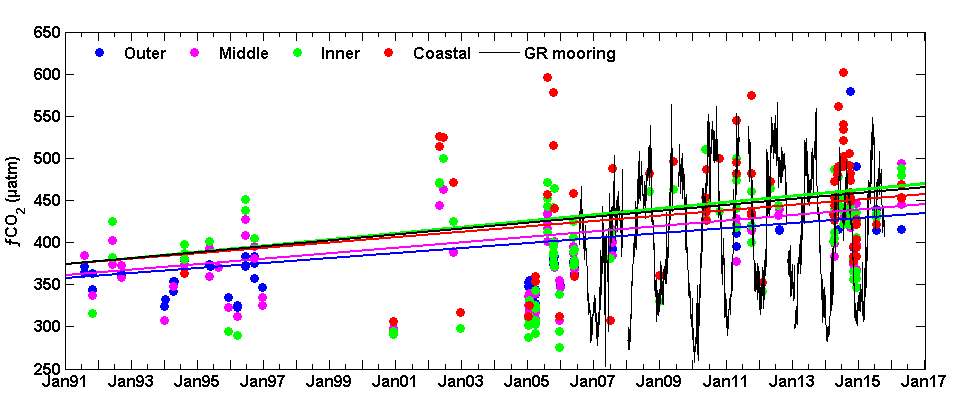

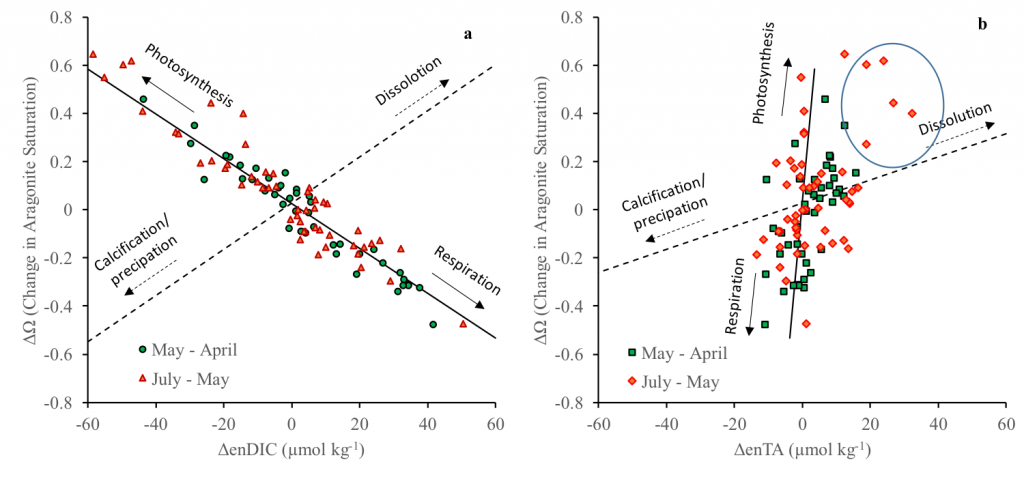

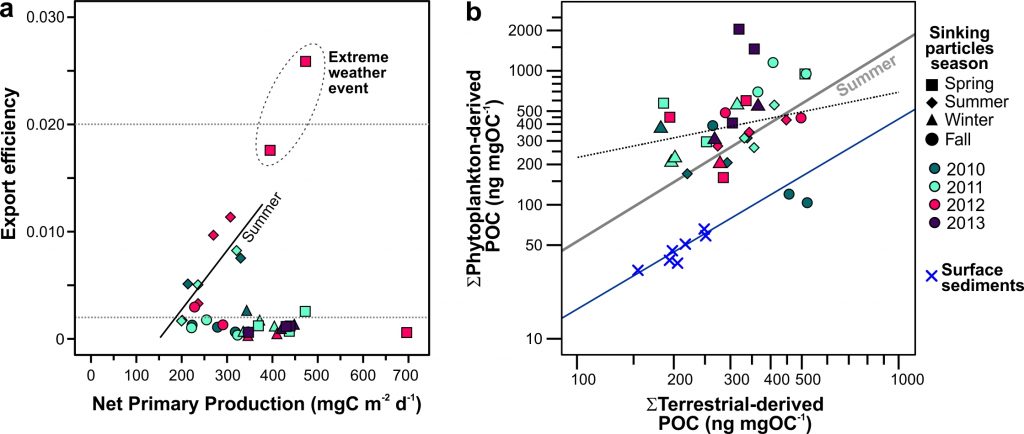

Figure Caption: a) Biplot of net primary productivity vs export efficiency (top and bottom horizontal dashed lines indicate threshold for high and low export efficiency regimes). b) Biplot of POC-normalized concentrations of terrestrial vs. phytoplankton-derived lipid biomarkers of the sinking particles collected in the deep Eastern Mediterranean Sea (Ierapetra Basin, NW Levantine Basin) from June 2010–June 2013, and surface sediments collected from January 2007 to June 2012 in the study area.

Both seasonal and episodic pulses are crucial for POC export to the deep Eastern Mediterranean Sea. POC fluxes peaked in spring April–May 2012 (12.2 mg m−2 d−1) related with extreme atmospheric forcing. Overall, summer particle export fuels more efficient carbon sequestration than the other seasons. The results of this study highlight that the combination of extreme weather events and aerosol deposition can trigger an influx of both marine labile carbon and anthropogenic compounds to the deep. Finally, the comparison of the sinking particles flux data with surface sediments revealed an isotopic discrimination, as well as a preferential degradation of labile organic matter during deposition and burial, along with higher preservation of land-derived POC in the underlying sediments. This study provides key knowledge to better understand the export, fate and preservation vs. degradation of organic carbon, and for modeling the organic carbon burial rates in the Mediterranean Sea.

Authors:

Rut Pedrosa-Pamies (The Ecosystems Center, Marine Biological Laboratory, US; Research Group in Marine Geosciences, University of Barcelona, Spain)

Constantine Parinos (Institute of Oceanography, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Greece)

Anna Sanchez-Vidal (Group in Marine Geosciences, University of Barcelona, Spain)

Antoni Calafat (Group in Marine Geosciences, University of Barcelona, Spain)

Miquel Canals (Group in Marine Geosciences, University of Barcelona, Spain)

Dimitris Velaoras (Institute of Oceanography, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Greece)

Nikolaos Mihalopoulos (Environmental Chemical Processes Laboratory, University of Crete; National Observatory of Athens, Greece)

Maria Kanakidou (Environmental Chemical Processes Laboratory, University of Crete Greece)

Nikolaos Lampadariou (Institute of Oceanography, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Greece)

Alexandra Gogou (Institute of Oceanography, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Greece)