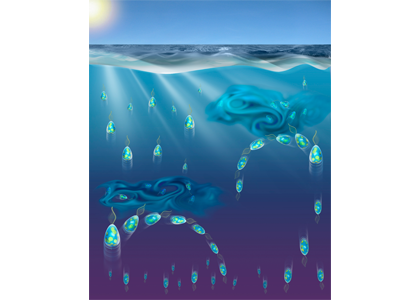

Antarctic shelf systems generate the densest waters in the world. These shelf waters are the building blocks of Antarctic Bottom Water, the ocean’s abyssal water mass. These bottom waters have the potential to sequester carbon out of the atmosphere for millennia. One such form of marine carbon is dissolved organic carbon (DOC). DOC is produced in the surface ocean via primary production and is the global ocean’s largest standing stock of reduced carbon.

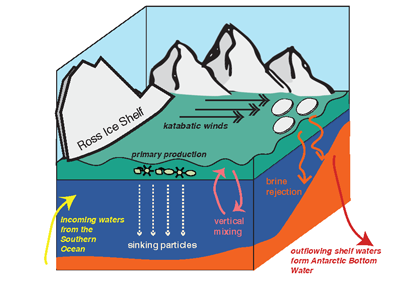

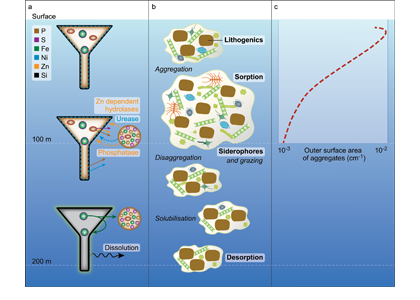

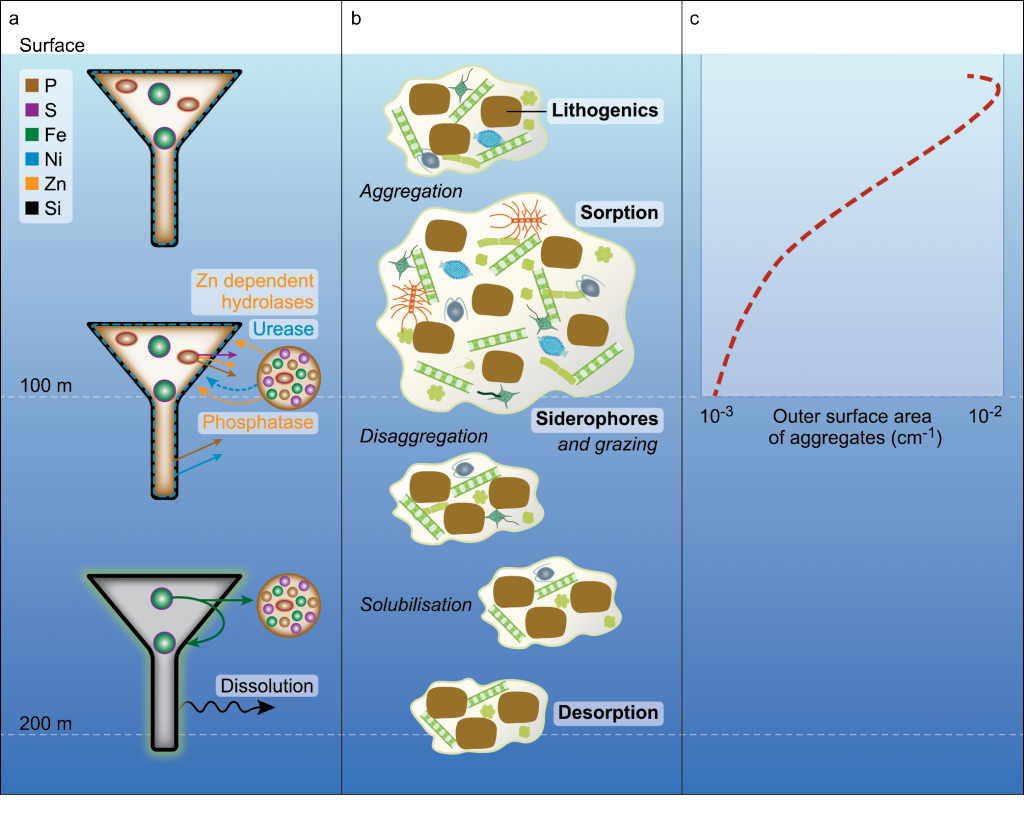

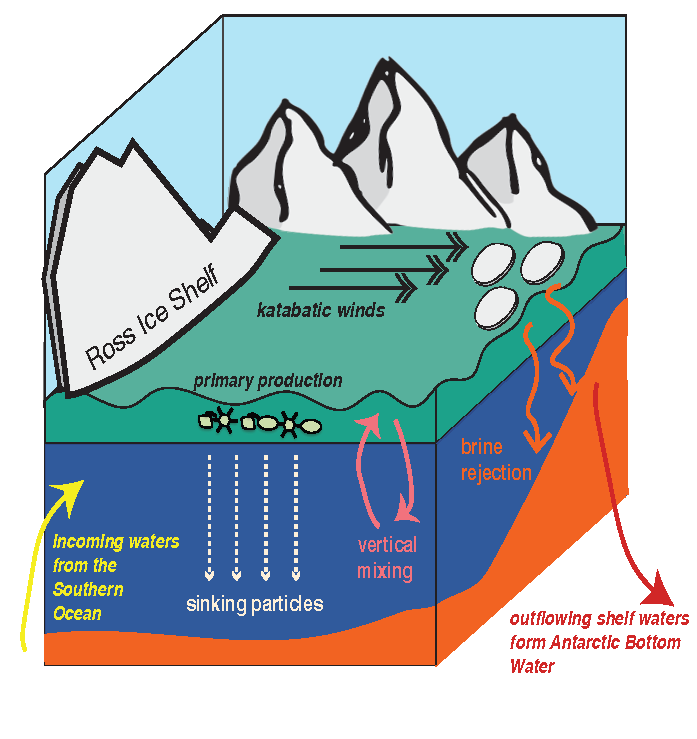

In a recent study, Bercovici et al (2017) used hydrographic and biogeochemical measurements to assess the mechanism that brings DOC into the shelf waters of the Ross Sea, the shelf system in the Pacific sector of Antarctica. These mechanisms include sinking particles, brine rejection caused by katabatic winds in the Terra Nova Bay polynya, and vertical mixing. This study revealed that DOC is primarily introduced into the deeper shelf waters via convective overturning and deep vertical mixing upon the onset of austral winter. Substantial DOC enrichment of shelf waters suggests that this carbon is exported off the shelf into Antarctic Bottom Water. However, this study finds much of the excess Ross Sea shelf DOC is actually consumed and remineralized to CO2 by deep microbial communities at the slope of the Ross Sea shelf, ultimately sequestering this carbon into the ocean’s interior.

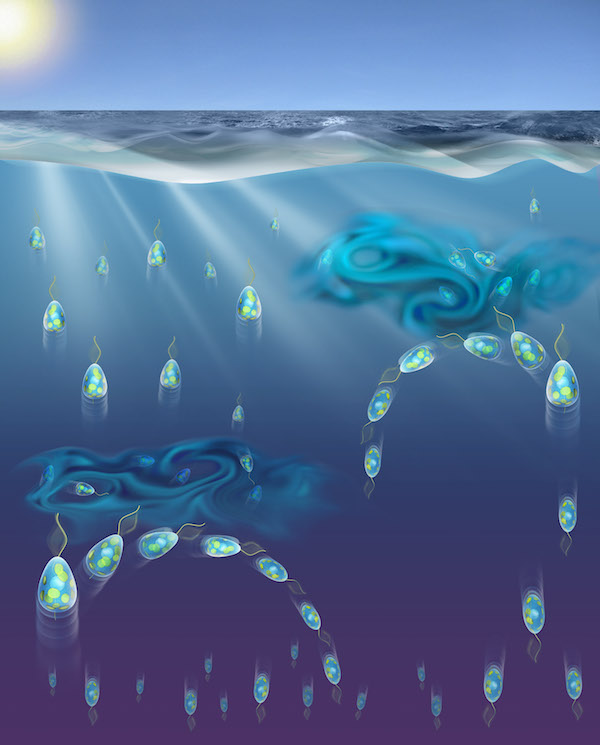

Physical and biological processes have the potential to introduce carbon into the dense shelf waters (blue) in the Ross Sea. Incoming waters (yellow) are modified from the Southern Ocean’s circumpolar waters. At the onset of winter, cooler temperatures and katabatic winds cause brine rejection. The rejection of brine, sinking particles and vertical mixing are all potential mechanisms for bringing DOC to the dense shelf waters. At the shelf slope, outflowing shelf waters ultimately contribute to Antarctic Bottom Water formation. This research furthers our understanding of global carbon cycling through demonstrating that Antarctic shelf systems have the potential to sequester organic carbon into the abyssal ocean.

Authors:

Sarah K. Bercovici (Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami)

Bruce A. Huber (Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University)

Hans B. Dejong (Stanford University)

Robert B. Dunbar (Stanford University)

Dennis A. Hansell (Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami)