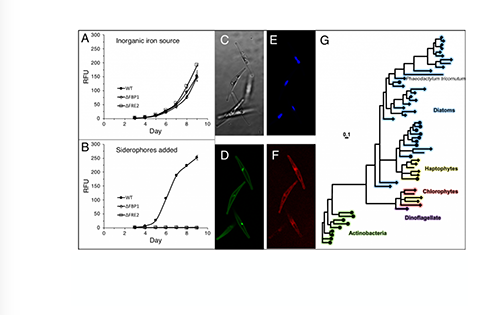

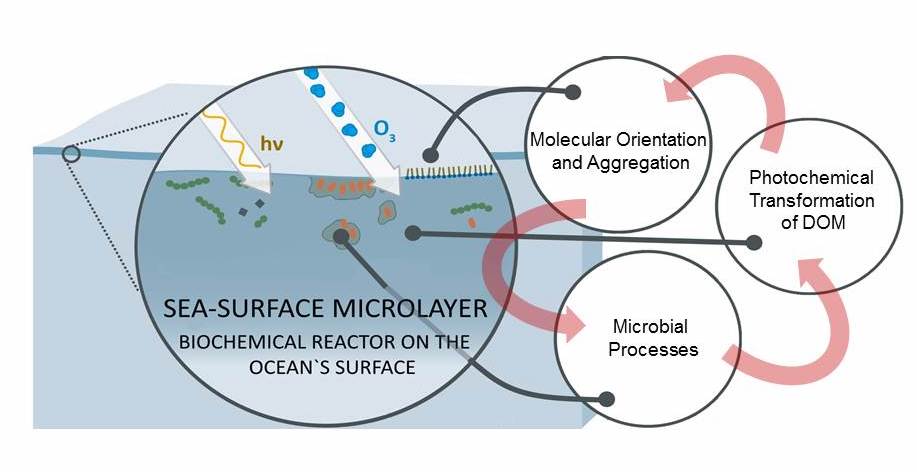

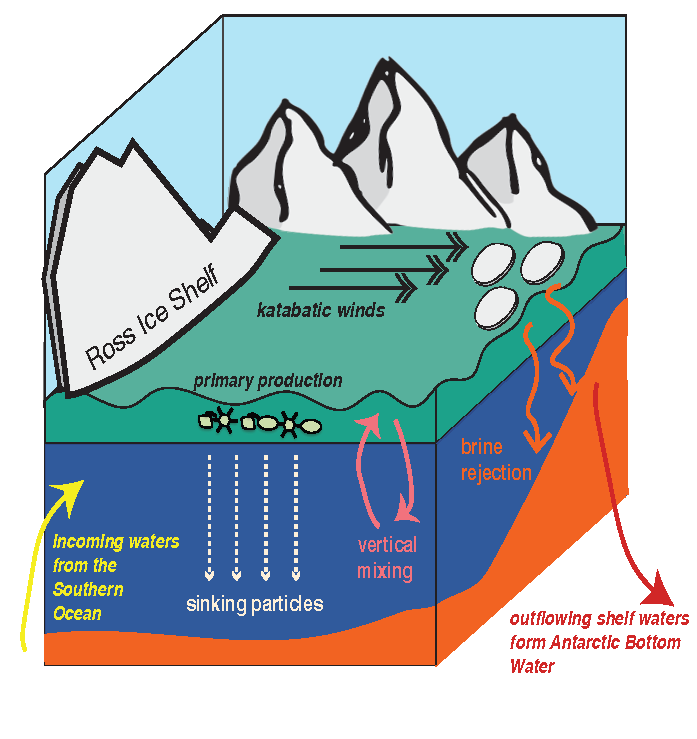

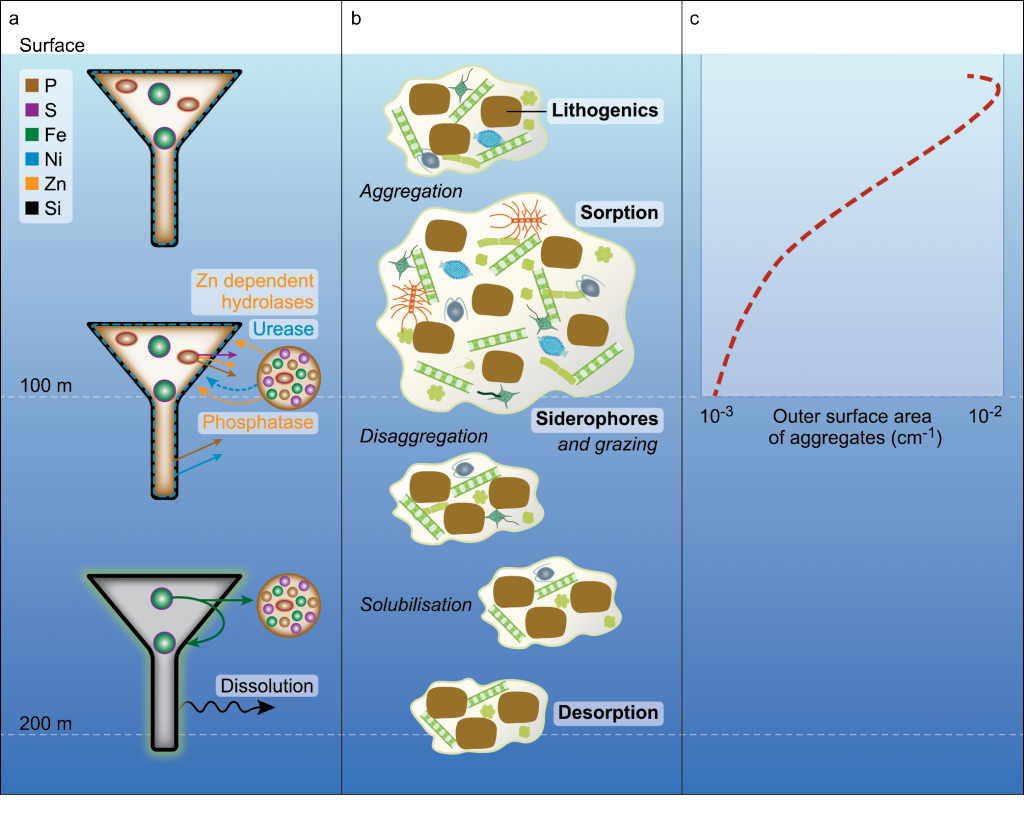

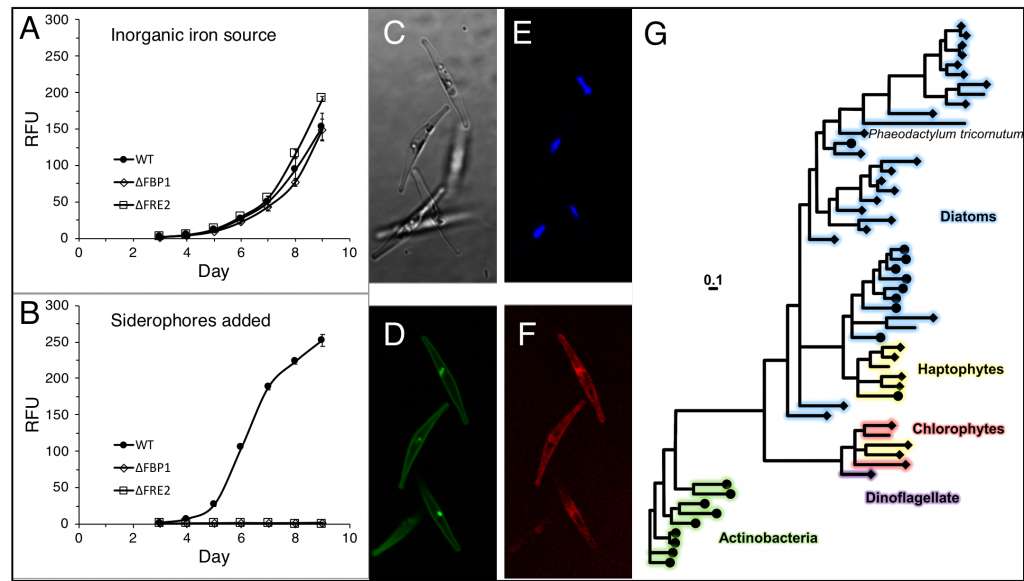

Since diatoms carry out much of the primary production in iron-limited marine environments, constraining the details of how these phytoplankton acquire the iron they need is paramount to our understanding of biogeochemical cycles of iron-depleted high-nutrient low-chlorophyll (HNLC) regions. The proteins involved in this process are largely unknown, but McQuaid et al. (2018) scientists described a carbonate-dependent uptake protein that enables diatoms to access inorganic iron dissolved in seawater. As increasing atmospheric CO2 results in decreased seawater carbonate ion concentrations, this iron uptake strategy may have an uncertain future. In a recent study published in PNAS, authors used CRISPR technology to characterize a parallel uptake system that requires no carbonate and is therefore not impacted by ocean acidification.

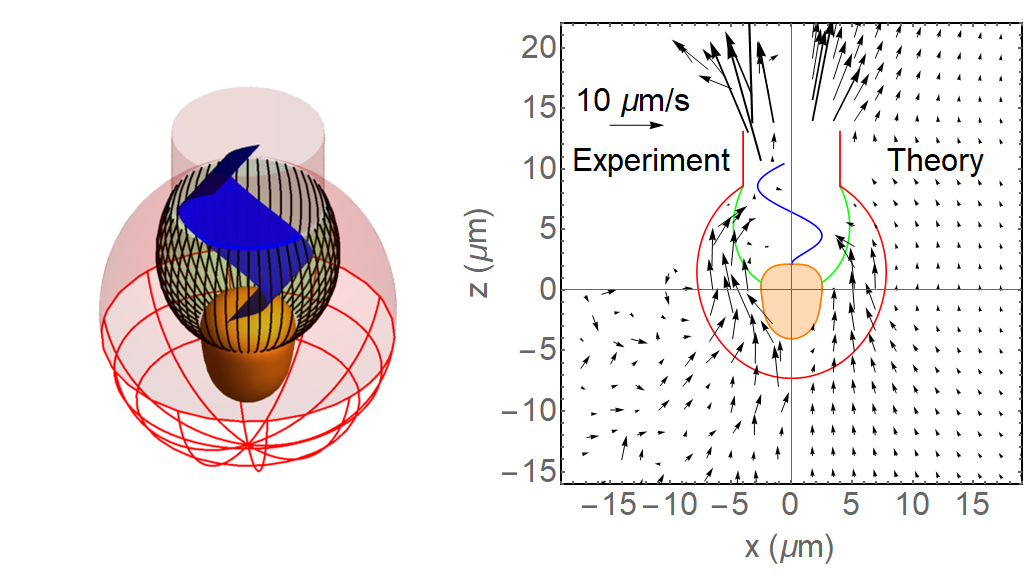

This system targets an organically complexed form of iron (siderophores, molecules that bind and transport iron in microorganisms) that is only produced by co-occurring microbes. Two genes are required to convert siderophores from a potent toxicant to an essential nutrient. One of these (FBP1) is a receptor that was horizontally acquired from siderophore-producing bacteria. The other (FRE2) is a eukaryotic reductase that facilitates the dissociation of Fe-siderophore complexes.

Figure caption: (A) Growth curves of diatom cultures ( • = WT, ◇ = ΔFBP1, ☐ = ΔFRE2) in low iron media. (B) Growth in same media with siderophores added. (C) Diatoms under 1000x magnification, brightfield. (D) mCherry-FBP1. (E) Plastid autofluorescence. (F) YFP-FRE2. (G) Phylogenetic tree of FBP1 and related homologs.

Are diatoms really stealing siderophores from hapless bacteria? The true nature of this interaction is unknown and may at times be mutualistic. For example, when iron availability limits the carbon supply to a microbial community, heterotrophic bacteria may benefit from using siderophores to divert iron to diatom companions. Further work is needed to understand the true ecological basis for this interaction, but these results suggest that as long as diatoms and bacteria co-occur, iron limitation in marine ecosystems will not be exacerbated by ocean acidification.

Authors:

Tyler Coale (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, J.Craig Venter Institute)

Mark Moosburner (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, J.Craig Venter Institute)

Aleš Horák (Biology Centre CAS, Institute of Parasitology, University of South Bohemia)

Miroslav Oborník (Biology Centre CAS, Institute of Parasitology, University of South Bohemia)

Katherine Barbeau (Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Andrew Allen (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, J.Craig Venter Institute)

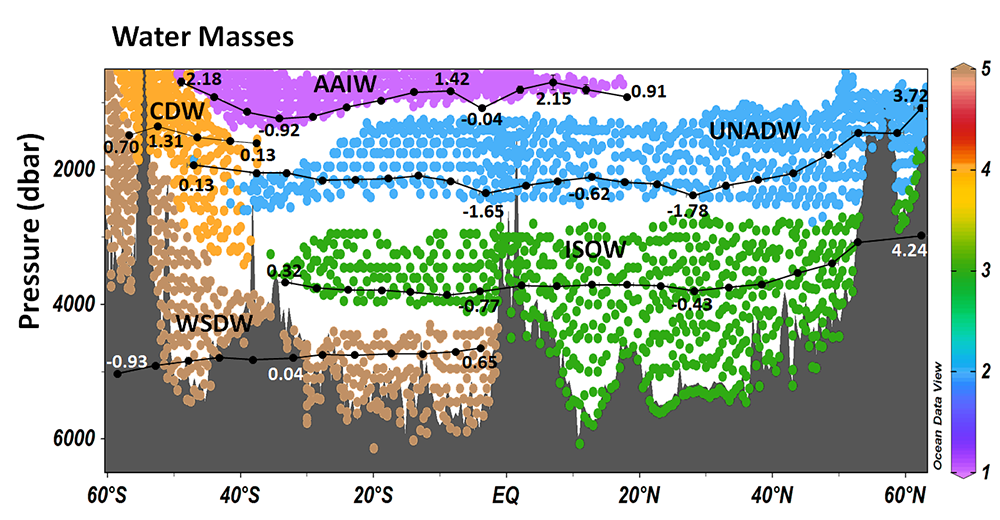

Also see joint post on the GEOTRACES website